A Secretary of State, a Google CEO, and an MIT dean walk into a bar…

Sometimes it behooves us to take a step back and view the forest and not the trees. In all this talk about models, materials, testing, and effects, one can be forgiven for asking, "what exactly is AI and is it a threat?" It is far easier to dismiss such broad viewpoints with the typical, "Hush. Adults are talking." But it is far more fruitful all around to take a moment and try to teach, for only in the process of teaching do we validate the models, materials, testing, and effects. A good starting point would be to listen in on the executive discussion as presented by "The Age of AI: And Our Human Future" (Kissinger, Schmidt, and Huttenlocher, 2021).

Henry Kissinger is a political doctorate who formerly served as a White House Secretary of State and National Security Advisor. Eric Schmidt is an engineering doctorate who formerly served as CEO of Google. Daniel Huttenlocher is the computing dean at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). From the introduction, the book is essentially a distillate of discussions among the three on where are we with AI and where might we be going. It is literally akin to having a guidance session for the chief executives on current and upcoming potentially disruptive technologies. The point here is not to review or critique but rather to listen in on what the perceived issues are and to add a clarifying perspective.

The authors discuss three representative current advancements:

- AlphaZero from Deepmind, a British research lab acquired by Google, recently created an advanced neural network to generate novel and extremely effective approaches to defeat all competitors in chess.

- An AI health science lab at MIT used a neural network to identify and generate a novel medicine named Halicin to treat diabetes.

- GPT-3 from an AI research company, OpenAI, is the 3rd version of their neural network to generate novel and effective human-like text.

Noting the author's backgrounds as an aside, there should be no surprise the examples draw from Google and MIT. Nevertheless, the perspective is clear. Rene Descartes famously said, "I think, therefore I am" (1637,1644). These models are performing tasks that heretofore could only be completed by humans. Could these and other examples be of AI thinking? If so, what does that make us humans? Should we, like Ken Jennings once wrote on Jeopardy, "…welcome our computer overlords?"

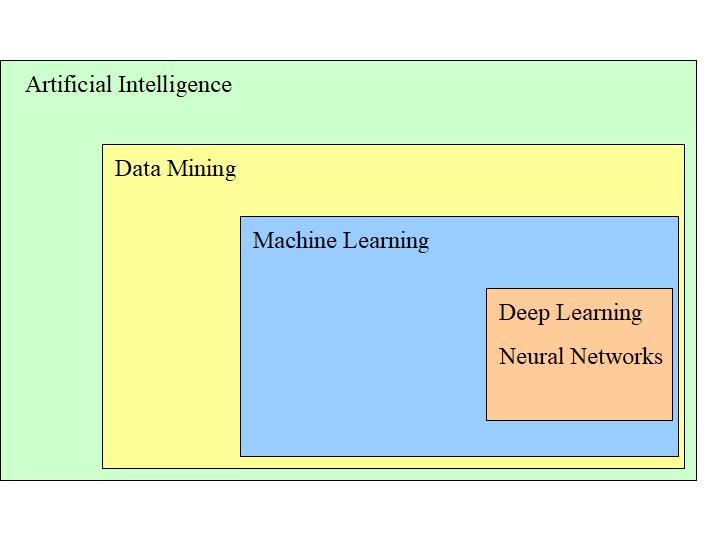

There follows a quick history of in-vogue phrases. Search engines (like Google) progressed from, "…human developed algorithms to organize, rank, and guide users…" to data mining. Sometime in 2015, Google progressed further to leveraging machine learning and allowing independent searches to be linked and tracked over time for a better user experience. Internal reviews show that search results are higher quality, but "developers [have only] a relatively vague understanding of why searches were producing particular results." By machine learning, they typically now mean neural networks. The latest name for neural networks since 2012 is deep learning. To translate these jargon to obvious concepts, (artificial) intelligence is now learning, it apparently has a dark (deep) brain-like structure, it works, and we cannot really control it. In this perspective, one can see that AI is dangerously scary.

Figure 1. AI terminology relations. AI is the most general concept of getting a machine to perform a task. In its basic form, a button press activates a door while a clapping sound or a timer turns off the toaster. Data Mining is the concept of summarizing historical actions into informative averages. Machine Learning attempts to self-generate the AI based on informative averages. For example, if button presses historically precede door activations, then a new button press should activate the door. Neural networks are a lattice of regressions (e.g. statistical averages) in multiple layers that can process a series of averages. A button press and a clap might do something different from a single clap. A deep learning neural network tends to have more layers, theoretically allowing more complex patterns.

Specifically, could a generator like GPT-3 create convincing hate-speech? Could enough hate-speech spark a riot, a revolution, or a civil war? Could it paralyze and polarize public opinion such that a disrupted population cannot effectively coordinate its defense against a blitzkrieg invasion?

"Abroad, [US social media platforms] are all increasingly treated (often without distinction) as creations of the United States [government] - although in many cases the US government's role was confined to staying out of their way." Other nations may view this deep, dark, dangerous entity as being under control of the US president -- or perhaps worse yet, not under the control of the US president or anybody. They would then feel justified in creating their own deep, dark, more dangerous versions under their control. Unsurprisingly, China or Russia would naturally figure into this discussion: "[foreign] governments have become increasingly outspoken regarding Chinese network platforms as potential or de facto extensions of the Chinese government's policy objectives."

With a National Security Advisor in the discussion, it is only natural to propose that the US Government step in and regulate all developments in AI. Some or all AI would be kept top secret, perhaps to be released as a counter stroke against a possible attack. Perhaps like nuclear weapons, there can even be an AI triad for Mutually Assured Destruction. Militarily, the US makes a distinction on use of AI in battlefield:

- AI-Enabled: the AI assists in high speed, low latency targeting but with a human-in-the-loop with weapons control.

- AI-Weapon: fully autonomous control where the AI can activate the weapon.

There is concern that other nations may lean towards AI-Weapons. If so, the discussion goes, shouldn’t the US consider doing the same to keep pace?

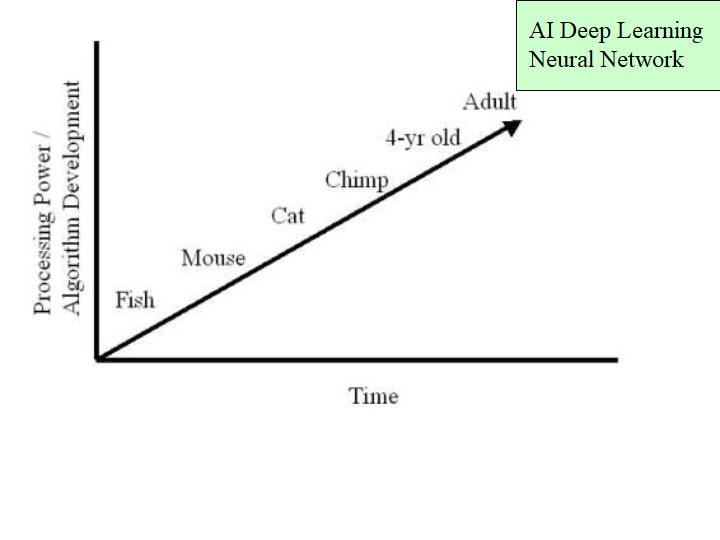

Figure 2. AI performance linear growth projections

If AI can eventually surpass human capabilities in all respects, would not restricting ourselves to AI-Enabled be unnecessarily tying one hand behind our backs? To summarize, AI is deep, AI is dark and dangerous, AI is here to stay, and we had best make our peace with letting it run the show or else someone else's AI will conquer us. And run the show anyway. i.e. Our AI is scary, but better our AI than their AI.

Now for the clarifying perspective.

First of all, vocabulary matters. Intelligence is intelligence. Artificial intelligence is artificial. Per Alan Turing and John McCarthy (1956), AI refers to "machines that can perform tasks that are characteristic of human intelligence." To date, there is no accepted clearly delineated theory what exactly is characteristic of human intelligence. AI computer programmers may claim those characteristics were clear and that AI critics - should we call them "AI-deniers" or "anti-AIs" - keep moving those goal posts.

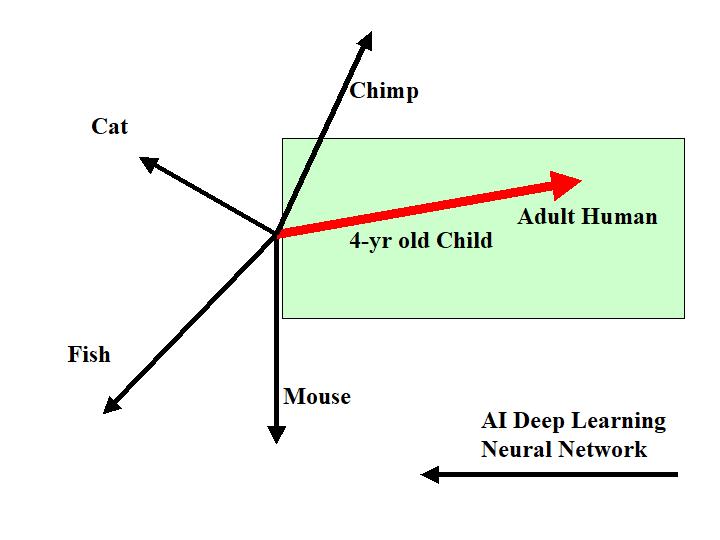

But the fact remains that having only computer AI researchers vs AI critics in the debate leaves for a very skewed and incomplete perspective. When inventing a car, we could not only include the car inventors and bike-riding environmentalist protestors in the discussion. Adding a politician and the car company's CEO (representing investors) would not necessarily be helpful either. We should include the drivers and precedent-setting horse and carriage operators as baselines. Similarly for AI, we would need to include a perspective from neuroscientists on how these theoretical models in figure 1 relate to what and where is intelligence. And we would need business managers or teachers to tie this in to empirical practice. Hint: we do not care about chimpanzee intelligence or fish intelligence. They are not relevant. They are out of scope. We only care about the human.

Figure 3. Non-Linear Intelligences. "If a tree falls in the woods and nobody hears it, did it really fall?" i.e. If nobody knows, and nobody cares, then it de facto may as well not exist. Here, fish or cat intelligence is not on the way to human intelligence and therefore do not serve as goal progression markers in any way. In this case, there is the possibility that AI Machine Learning Deep Learning Neural Network research - while useful in other ways - is not even on the path to human intelligence.

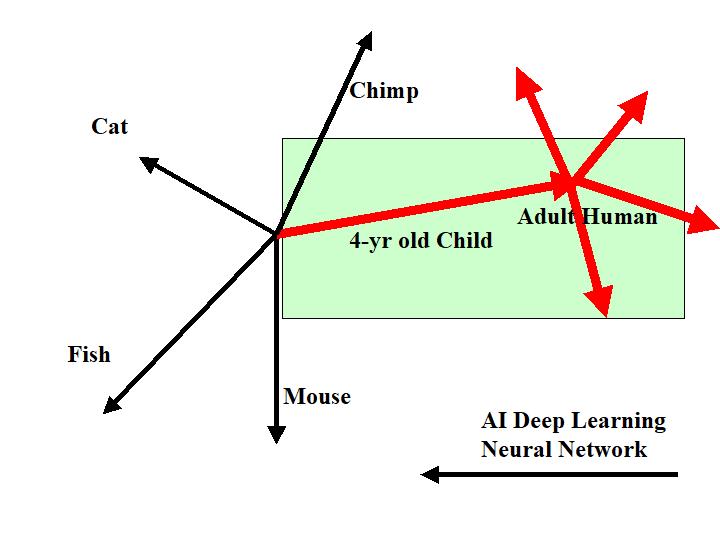

Psychology is the study of intelligence. Economics is the constrained study of rational intelligence. But we previously anchored intelligence from a practical business perspective of what makes a good employee. Colloquially, it describes "someone who knows what to do, does it our way, and attends to unforeseen opportunities." Earlier neuroscience work from 2009 onwards proposed the mechanisms as arising from selective attention, executive attention, and social learning - in turn centered on the hippocampus and regions of the prefrontal cortex.

From these two perspectives, intelligence then is not about what it stores or does or is programmed (genetically or computationally) to do but rather how it does it. It is more about mirroring and matching to do its task - whatever it is -- in the same manner and with the same intent as its connected team. Physically, intelligence is not a physical function embedded in a neuron or a neuron-like simulacrum but rather in the temporal active spaces between neurons - and by extension, between people. That is implied by the social learning. Thus, even asking how many neurons and synapses do we have in a human brain and how long before we can re-create a neuromorphic computer simulation of intelligence cannot be answered. If there are 86 billion neurons in a human brain with a quadrillion synapses, making a massive neural network of this size might not get us anywhere nearer to understanding or replicating human intelligence. Not only because there are massive numbers of hyper parameters and yet-to-be-discovered relationship models to choose how to fill those quadrillion synapses, but because none of us can be defined solely in isolation. Every good character story writer knows this: the protagonist behaves differently based on background connections to other characters. That's why so many stories have the protagonist as an orphan or otherwise on their own. It's easier but makes for a hollower character.

So those quadrillion synapses to fill? Multiply them by all the family, teachers, neighbors, competition, pets, and entire social environment. And they all change over time. That is social learning. It is not necessarily impossible or even more difficult technologically. But perhaps we need other characters on the team and not abandon the computer AI researchers to do it alone.

Figure 4. Non-Linear, non-stationary, and social learning intelligences.

Now thusly armed, we can revisit the first questions: are those GPT-3, AlphaZero and Halicin examples of human thinking, cogito ergo sum? Should we welcome our computer overlords?

Answers: not likely and not unless we want to. We could worship the button activated door opener or the voice sound activated toaster if we like, but nobody except our panicked neighbor is going to force us to do so. Unless of course our neighbor's name is Caligula and he has changed his mind from promoting his horse as overlord and wants now to promote a toaster. Stranger things have happened.

Now thusly armed, we can also partially answer the specific concerns: could AlphaZero and GPT-3 like capabilities allow us to saturate social media internet with hate-speech and cause riots or disruptions? The assumption being now that modern chatbot outputs are near indistinguishable from human writing, could chatbots successfully camouflage themselves and decoy humans?

A wonderful discussion and review of GPT-3 operations here with a commentary on the OpenAI team's challenges and constraints here provide some context. In evolutionary biology, there is the concept of convergence: different origins evolving similar analogs, yet remaining distinct. Applied here, humans can make incendiary speech to cause human riots. If a neural network creates incendiary speech, can that cause a human riot? Answer: yes but also no.

In this regard, the intent of this question is not really about how smart or advanced AlphaZero or GPT-3 are - undoubtedly they are amazing tools and equipment. Think of them as being stealth fighters with advanced radar guided, decoy-enabled missiles or stealthy nuclear submarines with guided torpedoes. But frankly, the actual focus of the question is on how stupid can the target humans be to have a riot? These specific concerns are about effects more so than causes.

In the United States, "Buy Tea in Boston Harbor" or "All Lexingtonians and Concordians are to surrender firearms" started a revolution in 1775. "States rights" vs "Abolition" started a civil war in 1861. Are we polarized today? How about that time in 1856 when a Preston Brooks (Democrat) stormed from the Representatives chamber, down the hall, burst into the Senate with an armed accomplice, and raised his walking stick to repeatedly beat Senator Charles Sumner (Republican) such that Sumner was out for years recovering. And Preston Brooks was re-elected by his constituents. Afraid that a computer-generated inflammatory essay could spark a rebellion? How about that historical Chinese classic (by Shi Nai'an, 1300?, English version, 1933) where a random peasant farmer named Fang-La led a massive rebellion in China. His casus belli? He interpreted the stars above his head in his reflection on a river as a message from Heaven that he was meant to be the emperor.

Many things can spark or precede a dangerous riot. But the credit assignment problem of whether a generative neural network is solely responsible as opposed to being the match that lit the powder keg requires thought and manipulation via social learning which requires mirroring on human terms. In contrast, the base origin for much of modern AI and Machine Learning is directory search. There are discriminator classifiers whose research goal is to categorize existing documents, for example, by relevance to a query. And there are generators whose research goal is to create new documents as if from the same pool of the query. As the GPT-3 name shows, Generative PreTrained Transformer version 3 is a generative neural network that focuses on generating text from a query. AlphaZero uses both a generator and a discriminator in a GAN setup. But without a working definition of intelligence, neither of these likely desired or even could be geared towards understanding or emulating conscious thought.

With those answers, we can address the final remaining proposals that the US Government should be involved as a military security entity. Is it dangerous? Do we need to go AI-enabled or AI-weaponized? Do we need AI to defend against AI?

The answer is a resounding no.

A few sample viewpoints from the US Navy:

In summary, the Navy viewpoint appears to share the same concern as the recent Google viewpoint on AI that "…developers [have only] a relatively vague understanding of why searches were producing particular results." While the military as super-user has long been an advocate for AI, it appears strongly in favor of AI-enabled and not AI-weaponized. This resonates again with business management stating a preference for "values over performance." Fast, smart, productive employees are useless if they perform their tasks in contravention of our policies and breach of trust with our customers. While a hair trigger on the weapon allows for a faster response that is "good for us," there are a number of institutions - courts and constitutional rights come to mind - whose purpose is to defend against those who would use "good for you" as an excuse to impose tyranny. So that is an argument that the costs and risks of an AI-weapon, whether ballistic or textual, are not worth the gain.

To put paid to this argument, we finally consider if there is truly any gain from setting an AI-weapon at all. To answer this, it again behooves us to take a step back and view the forest rather than the trees. But this time, over time itself. New and novel AI capabilities can admittedly seem scary. But what if we realize we have already had them for some time? A fast, automatic AI-weapon can activate with no human intervention. We call them land mines. A voice activated AI takes in a series of sounds and performs some function. We call that The Clapper from the 1980's. A car uses AI to automatically control steering and acceleration at driving speeds. Automatic airplane landing systems have been controlling planes at flying speeds since the 1950's.

Neil deGrasse Tyson (2014) illustrates how to find where we are in development of a technology. At first, the Global Positioning System (GPS) led the way. It was pioneering, funding it was a challenge, nobody believed in it, even the military wanted to stay with Inertial Navigation Systems (INS). Now it proliferates everywhere such that at a meeting with European aerospace planners in Brussels about their Galileo system, deGrasse Tyson recalls

"So we were kind of worried: what happens if they finish Galileo, equip European planes with it, and announce that we have to have it to fly into European airspace… So, while we were trying to understand the situation, the Europeans were sitting there looking fairly smug, especially one particular guy. I'm pretty sure our chairs were lower than theirs, because I remember looking up at them… And I got livid. Why was I livid? Because we were sitting around a table talking about aerospace product as though it were soybeans - what are the trade regulations, the tariffs, the restrictions; if you do this, then we'll do that. And I'm thinking, There's something wrong here… If you’re truly on the frontier, you don't sit at a table negotiating usage rights."

His point on the scariness of AI-weapons might be that they are not what is scary. Perhaps what is truly scary is that we have come to some form of stagnation where we can even propose that the US Government can or should regulate its research and usage.

If so, then this again matches the common refrain that researchers cannot explain why or how AI neural networks work. This matches again with the expected outcome of having only "…computer AI researchers vs AI critics" alone and abandoned in the discussion with the CEO and politicians. The existing work is amazing and we may need to use it. But the actual question should be, "What do we need to remove the Artificial from AI?"